OCD Symptoms and Behavioral Patterns

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a complex mental health condition defined by intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors that can feel impossible to ignore. These patterns are not simply habits: they are rituals performed to relieve excessive anxiety. By breaking down the symptoms, emotional triggers, and cognitive patterns of OCD, people with this condition can better understand what it looks like in everyday life and how to manage it effectively.

Although symptoms can sometimes be aggressive, with the right treatment and support, many people experience a significant reduction in symptoms and improved quality of life.

Defining OCD Symptoms and Behaviors

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms encompass both obsessions, which include intrusive thoughts, urges, or images, as well as compulsions, which include repetitive behaviors or mental thoughts. These compulsive behaviors are performed in response to obsessions or according to rigid rules. They are often aimed at reducing distress or preventing feared outcomes. They often feel involuntary, and such symptoms can disrupt daily life [1].

The four most common symptom dimensions that impact OCD states include:

- Contamination and Cleaning: This includes fear of germs and illness, which often leads to repetitive washing or avoidance of things and places perceived as dirty.

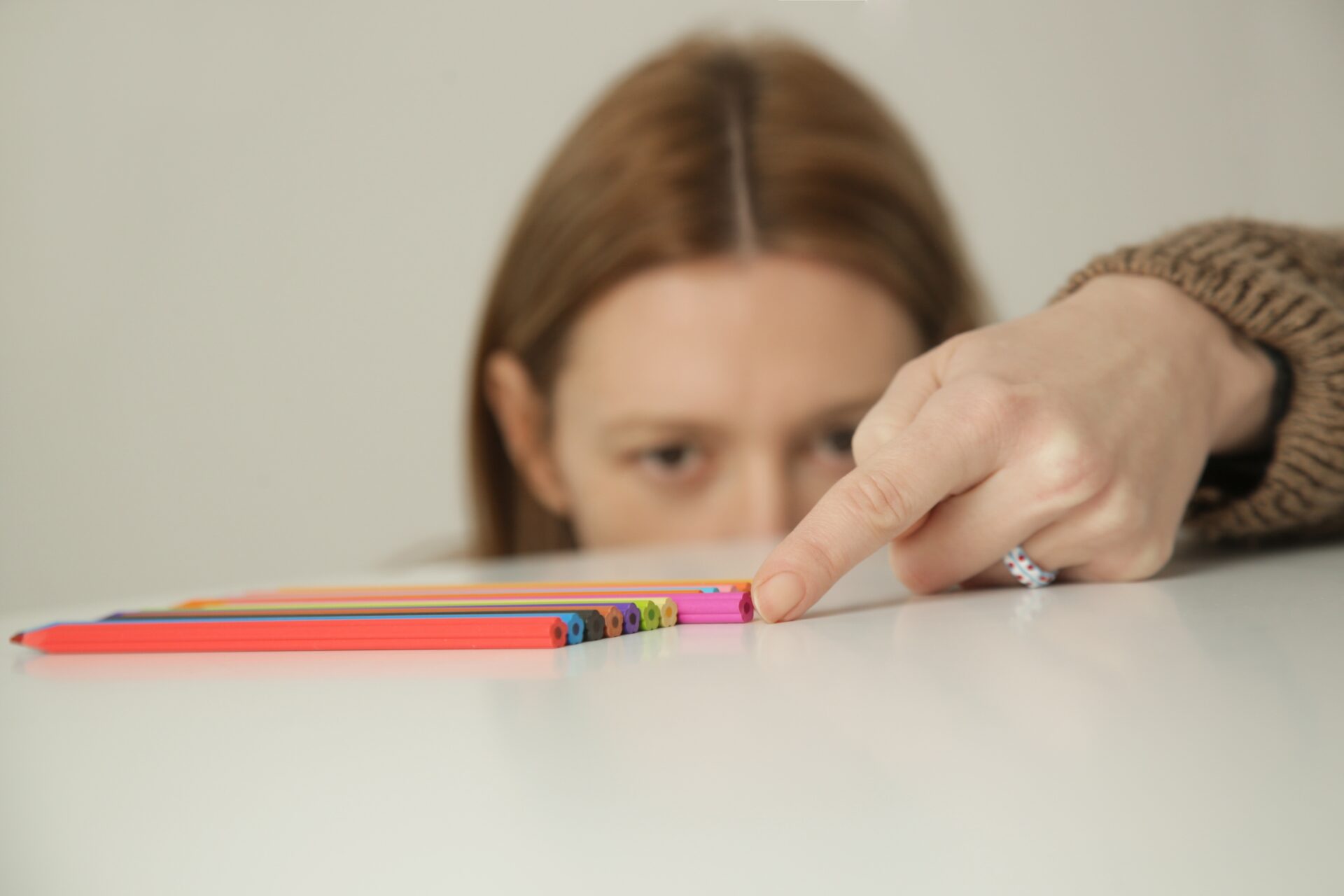

- Symmetry and Ordering: This encompasses a need for balance and exactness, which often leads to behaviors such as constant counting and rearranging.

- Intrusive Thoughts: These thoughts are intrusive and distressing, and they can be aggressive, sexual, or even religious in nature.

- Harm and Checking: This dimension involves a fear of causing accidental harm to oneself or others, and it often results in one checking things repeatedly.

How Compulsions Function in OCD

To escape the anxiety triggered by intrusive thoughts, people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) often feel an intense urge to do something quickly and repeatedly. These compulsions aren’t mere preferences. Instead, they are strategies to reduce distress or prevent imagined harm.

Compulsions can be:

- Visible Behaviors: These behaviors can include scrubbing hands, checking locks, or precisely arranging items.

- Mental Rituals: These can involve silently repeating words, counting, or neutralizing “bad” thoughts with “good” ones.

Compulsions can persist in people with OCD because they bring temporary relief. However, they also reinforce the fear that obsessions are dangerous. Over time, this cycle becomes self-sustaining as obsession triggers compulsion, which lowers anxiety but strengthens the disorder overall [1].

Another common form of compulsion that can be distressing for people with the condition is tics. They are sudden and recurring involuntary spasms that can take the form of both actions and words. OCD and tic disorders are two distinct conditions, but they can sometimes coexist or occur together.

How They Impact Daily Life

Rituals can consume several hours each day, interfering with daily activities and relationships. Many people struggle to keep up with their work, studies, and social commitments as compulsions take priority [1]. For people with the condition, this can result in distress and dysfunction in multiple areas of life.

Emotional and Cognitive Patterns in OCD

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is not limited to observable behaviors, as it also involves specific cognitive and emotional responses. OCD can bring intense emotions like fear, guilt, or shame, especially when intrusive thoughts feel deeply personal.

For many people, these thoughts are distressing because they clash with their core values. For instance, someone might imagine harming a loved one, even though they would never act on it. The emotional weight of these thoughts can feel overwhelming [2].

How the Brain Handles Obsessions in OCD

People with OCD often believe their thoughts are dangerous or morally wrong. This leads to rituals designed to “cancel out” the thought. For instance, someone may mentally repeat prayers to ease guilt about a religious image.

The multidimensional model of OCD identifies some of the patterns that keep this cycle going:

- Inflated Responsibility: This involves feeling responsible for preventing harm.

- Perfectionism: One may feel they need things to be exact or “right” with perfectionism.

- Thought-Action Fusion: This is the belief that having a bad thought is as bad as carrying out the thought.

- Intolerance of Uncertainty: With this pattern, one may have issues coping with doubt or not knowing something for sure.

These thinking patterns increase anxiety and make rituals feel necessary, even when they interrupt daily life or cause significant distress [2].

Behavioral Responses and Avoidance in OCD

In addition to compulsive rituals, many people with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) engage in avoidance behaviors. With this type of behavior, one attempts to reduce their exposure to triggers. This may include avoiding certain places, people, or situations altogether.

While avoidance offers short-term relief, it reinforces the belief that the threat is real. Over time, it can limit social interactions and increase isolation.

Acceptance vs. Suppression of Intrusive Thoughts

Researchers have observed three ways people try to manage intrusive thoughts: by suppressing the thoughts, distracting themselves, or accepting the thoughts. One study found that when people tried to suppress their thoughts, those thoughts came back more frequently and felt more distressing. Suppression made the unwanted content more persistent and harder to ignore [3].

This study found that accepting and acknowledging the thought in question without reacting to it was more effective. People who practiced mindfulness and acceptance reported lower distress and fewer intrusive thoughts over time. This approach teaches the brain that not all thoughts are dangerous or worth reacting to. This helps weaken the OCD cycle by forming new and less upsetting thought patterns [3].

How Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Disrupts Daily Life

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can interfere with the ability to stay present and follow through on daily tasks. That’s because OCD can influence decision-making by causing one to become excessively focused on details and fear making mistakes.

For example, some people struggle to leave the house on time or finish assignments because they feel stuck in a cycle of checking things or seeking reassurance about a fear. Others avoid important conversations or cancel plans when anxiety builds. As rituals take up more space, important daily routines may start to break down and relationships can suffer as a result.

What Brain Imaging Reveals

Brain scans show that OCD is linked to irregular activity in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuit. This part of the brain plays a role in how people filter information, control impulses, and shift between tasks.

When the circuit misfires, the brain can get “stuck,” making it harder to let go of intrusive thoughts or stop repetitive behavior. These findings help explain why OCD symptoms can feel so automatic and difficult to override [4].

Managing Obsessive Thoughts and Compulsions

The most effective treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) helps the brain stop reacting to fear with rituals. One of the leading approaches is exposure and response prevention (ERP). This therapy teaches people to practice facing their triggers without giving into compulsions and the uncomfortable feelings they bring up. Over time, they notice that their anxiety loses its intensity and rituals become easier to resist [5].

When Medication Can Help

Doctors often prescribe selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to reduce obsessive thoughts and lower overall anxiety. This kind of medication can create enough mental space for therapy to work and ease the intensity of compulsions. It can also support long-term recovery, especially in moderate to severe cases.

When standard medication doses aren’t effective, providers may adjust the dosage or add another option to improve results. It’s important to note that many people may have to try a few different approaches to treatment before finding a fit that brings them symptom relief [5].

What To Do Between Sessions

Some people find it helpful to use coping tools between appointments, especially if they attend therapy sessions that use approaches like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Some helpful strategies include:

- Mindfulness: This revolves around observing thoughts without reacting.

- Reframing: This process involves labeling intrusive thoughts as symptoms, not facts.

- Delaying: Drawing out the time before performing a compulsion can weaken the habit loop.

These strategies work best when guided by a therapist. On their own, they may not be strong enough to disrupt long-standing patterns [5].

When to Seek Professional Support

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) tends to increase in severity over time, and what starts as a quick ritual can grow into hours of lost focus or rising anxiety and panic.

Reaching out to a mental health professional can lead to a proper diagnosis. They can also create a treatment plan that matches one’s specific experience. Early intervention often leads to better outcomes and makes it easier to interrupt the cycle before it takes over more areas of life.

How Clinicians Approach OCD Treatment

Mental health professionals use structured interviews and assessments to understand the unique way that OCD shows up in each person’s life. This helps them rule out other conditions like anxiety disorders or tics.

It also allows them to identify which symptoms are most disruptive and build a treatment plan that addresses specific challenges with the right medication. Overall, support works best when it’s built around the whole person and not just the diagnosis [6].

Moving Toward Recovery and Support

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can be overwhelming, but recovery is within reach. Many people regain a sense of control once they begin treatment that fits their needs and experiences. The goal isn’t to eliminate every intrusive thought: instead, recovery focuses on responding to those thoughts in ways that reduce anxiety and restore freedom.

Treatment often works best when it combines therapy that targets symptoms through approaches like exposure and response prevention (ERP) with medication that reduces the intensity of anxiety and intrusive thoughts. It’s also most effective alongside social support from loved ones, support groups, or mental health communities.

Over time, people can build routines that are not shaped by fear. They can lead lives that are not impacted by distressing symptoms. With consistent treatment and the right support network, it becomes possible to return to work, reconnect with loved ones, and reclaim the parts of life that OCD once disrupted [6].

- Leckman, J. F., Grice, D. E., Boardman, J., Zhang, H., Vitale, A., Bondi, C., … & Pauls, D. L. (1997). Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(7), 911–917. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9210740/. Accessed May 4, 2025.

- Mataix-Cols, D., Rosario-Campos, M. C., & Leckman, J. F. (2005). A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 228–238. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15677583/. Accessed May 4, 2025.

- Najmi, S., Riemann, B. C., & Wegner, D. M. (2009). Managing unwanted intrusive thoughts in obsessive–compulsive disorder: Relative effectiveness of suppression, focused distraction, and acceptance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(12), 1024–1032. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S000579670900059X. Accessed May 4, 2025.

- Saxena, S., Bota, R. G., & Brody, A. L. (2001). Brain-behavior relationships in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 6(2), 82–101. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11296309/. Accessed May 4, 2025.

- Seibell, P. J., & Hollander, E. (2014). Management of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(10), 1026–1033. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25165567/. Accessed May 4, 2025.

- Fenske, J. N., & Petersen, K. (2015). Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Diagnosis and management. American Family Physician, 92(10), 896–903. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26554283/. Accessed May 4, 2025.

The Clinical Affairs Team at MentalHealth.com is a dedicated group of medical professionals with diverse and extensive clinical experience. They actively contribute to the development of content, products, and services, and meticulously review all medical material before publication to ensure accuracy and alignment with current research and conversations in mental health. For more information, please visit the Editorial Policy.

We are a health technology company that guides people toward self-understanding and connection. The platform provides reliable resources, accessible services, and nurturing communities. Its purpose is to educate, support, and empower people in their pursuit of well-being.

Areesha Hosmer is a writer with an academic background in psychology and a focus on Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

Holly Schiff, Psy.D., is a licensed clinical psychologist specializing in the treatment of children, young adults, and their families.

The Clinical Affairs Team at MentalHealth.com is a dedicated group of medical professionals with diverse and extensive clinical experience. They actively contribute to the development of content, products, and services, and meticulously review all medical material before publication to ensure accuracy and alignment with current research and conversations in mental health. For more information, please visit the Editorial Policy.

We are a health technology company that guides people toward self-understanding and connection. The platform provides reliable resources, accessible services, and nurturing communities. Its purpose is to educate, support, and empower people in their pursuit of well-being.